“I Have Lost Everything”: Iranian Students with Valid Visas Sent Home Upon Arrival at US Airports

- Ebby Abramson

- Jan 29, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 12, 2022

Last September, Reihana Emami Arandi boarded a flight from Tehran and made her way to Boston, eager to study theology at an Ivy League university.

After nearly 100 days of vetting and background checks by the US government, the 35-year-old was bound for a graduate program at Harvard Divinity School with a student visa in hand. However, when she arrived at Boston Logan International Airport, she was promptly pulled aside by US Customs and Border Protection officers for additional questioning.

They led her to a separate area of the airport, where an officer inquired about her travels, her work experience, her family, her studies, and what her cellphone number was in Iran, she said. The officer searched her luggage, pulled out her Quran, and asked what it was.

“He then asked me what Iranian people think about the explosion in Saudi Arabia,” she said, referring to the September 14 drone strike on a Saudi Arabian oil facility for which the Iran-backed Houthi movement in Yemen claimed responsibility.

“I explained I didn’t know much and that people generally hoped the situation would get better.”

He inspected her laptop and phone. About eight hours later, after being fingerprinted and having her photo taken, she was on a flight back to Iran, unable to enter the country for five years. Customs officers had concluded that she planned on not just studying in the US but staying here, Emami Arandi said—a charge she called “far from reality.”

Her case isn’t an aberration. At least 15 other Iranian students with valid visas have been sent home upon their arrival to American airports since last August, immigration attorneys said. In addition, about 20 more students in Tehran were unexpectedly prevented from boarding US-bound flights. Many said they were not given a reason for being refused entry.

Several of the students were held up in Boston, advocacy groups said, noting that they have received multiple complaints about one specific CBP officer there. A CBP spokesperson said they could not discuss individual cases, but that “simply having a valid visa does not guarantee entry into the US.”

“CBP officers make admissibility decisions based on whether an individual can overcome ALL grounds of inadmissibility,” the agency said in an email, adding that there was no new directive ordering additional questioning or scrutiny of Iranians with student visas.

“Regardless of having the appropriate documents, if an officer determines an individual cannot overcome all of those grounds, they will be refused entry into the US.”

University officials and Iranian American groups said they don’t know what prompted what they regard as a sudden crackdown on Iranian students. Their concerns have arisen amid mounting political tensions between the Trump administration and Iran, culminating in the US drone strike that killed Iranian General Qassem Suleimani on January 3 and an Iranian missile strike in response.

Advocates said it’s unclear how the countries’ strained relations may factor into denying Iranian students entry to the US, but they point out that Iranians’ difficulty traveling to the US has not been limited to students on visas. Earlier this month, more than 60 Iranians and Iranian Americans were questioned for hours at the Washington-Canada border as they tried to return home.

“This number is alarming,” said Ali Rahnama, an attorney with the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans, which has been tracking the cases.

“Yes, we have dealt with people being deported in the past, but the numbers weren’t big,” he continued. “Iranian students have been coming to study here for 70 years—the revolution didn’t change that, the wars with Iraq and Afghanistan didn’t change that.”

One of the top students in his class the University of Tehran, Amin landed in Georgia on January 1 with hopes of earning his PhD at the University of Florida. But when he reached the airport in Atlanta, officers questioned why he had not disclosed an old school email address or one of the research papers he’d written on his visa application.

Amin, 34, began to shake and cry when he learned he had been found “inadmissible.” That’s when his “three-day nightmare” began, he said.

An officer told him he had to return to Iran on the same flight he arrived on. That flight would not be available for two days, he recalled the officer saying—and he couldn’t be held at the airport for more than 24 hours. Amin said officers put him in a holding cell for six hours before cuffing him and moving him in chains to a detention facility in Georgia.

“They are playing with people’s futures,” Amin said. “Aside from being Iranian and a student, what did I do?”

Another Iranian student, Mohammad Shahab Dehghani Hossein Abadi, was denied entry to the US earlier this month despite previously having studied at Northeastern University for two semesters. He had traveled to Iran to visit his family, his attorney said.

Dehghani, 23, was placed on a flight from Boston to France despite a judge’s order that his removal be stayed for 48 hours or until further order from the court.

Stephen Yale-Loehr, a professor at Cornell University Law School, said the difficulties that Iranian students currently face are part of a “disturbing trend we’ve seen before.” After Iranians stormed the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, he said, Iranian students in the US had to register with immigration officials or risk deportation.

More recently, the detention of “people of Muslim descent” after the September 11 terrorist attacks “failed to yield any significant results in finding and deterring other terrorists,” Yale-Loehr said.

Mahsa Khanbabai, chair of the New England chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Assn., said she’s been trying to figure out why students have been having problems since October. Some, she said, were accused of “immigrant intent,” or planning to overstay their visas and live in the US.

“These charges don’t make sense,” she said. “They are students engaging in research. So why CBP is looking to institute this extreme, harsh law against them, I don’t know.”

Customs and Border Protection was given the authority of “expedited removal” in 1996, said Kerry Doyle, one of the attorneys representing Dehghani. The move granted CBP the power to order an immigrant removed without any court review, she said.

“But the only people who fit into that category are only supposed to be people who show up with some kind of fraud or immigrant intent, like if you show up to the airport with everything and your kitchen sink with no return ticket,” she said.

CBP’s use of expedited removal in the case of students like Dehghani is “completely improper,” she said.

“They seem to be digging and searching for an excuse,” Doyle said. “They’re using this great power they have inappropriately and illegally.”

Similar incidents continue to pop up across the country—most recently in Detroit, where an Iranian student bound for graduate school at Michigan State University was sent back to Iran on his birthday.

Alireza Yazdani Esfidajani, 27, was detained by CBP officers upon his arrival at Detroit Metro Airport on Sunday afternoon, his attorney Ghazal Nicole Mehrani said. After about six hours of questioning, he was transferred to Monroe County’s jail, where he was held until around noon Monday, Mehrani said.

CBP officers deemed him “inadmissible,” she added, but it wasn’t clear why.

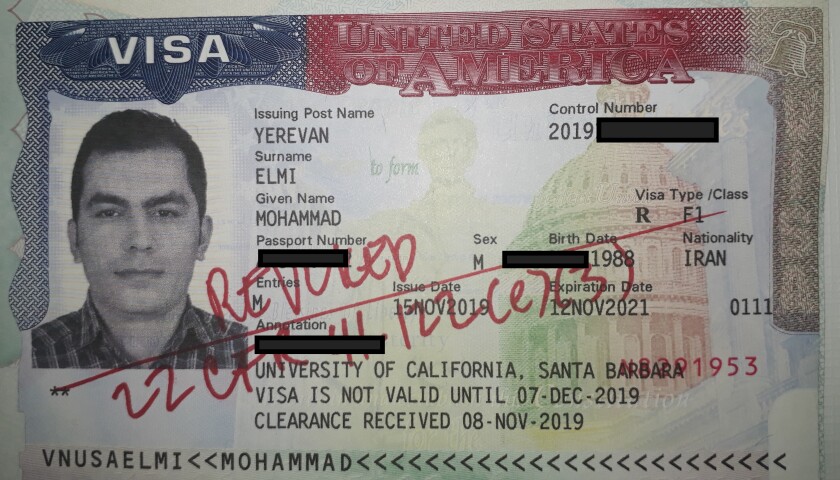

When Mohammad Elmi disembarked at Los Angeles International Airport on December 13, two CBP officers were waiting for him. They escorted him to a room, questioned the purpose of his visit, and checked his phone, bags, shoes and belt. He was not allowed to make a call for several hours.

Elmi was on his way to reunite with his wife, Shima Mousavi, and to pursue his PhD in electrical engineering at the UC Santa Barbara. Mousavi was already attending Antioch University Santa Barbara on a student visa—a school she transferred to so the pair could live in the same city.

‘I have lost my job. I have lost my money. I have lost everything.’

MOHAMMAD ELMI

Elmi told the officers that during his mandatory military service in Iran he served in the Artesh, or arm —a branch separate from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which the US government has designated as a terrorist organization.

The 31-year-old then was interviewed by another CBP officer, who told him it would be best if he withdrew his application for a visa in order to prevent being denied entry. If he was refused entry, the officer told him, Elmi would not be allowed to enter the US for five years.

The officers, Elmi said, were aggressive: one yelled when he asked whether he could access his luggage; another told him he would have to pay $3,750 for his flight back to Iran. He already had spent $4,000 and gone through eight months of administrative processing to get to the US.

“They behaved like I am a terrorist,” Elmi said.

Elmi had always planned on returning to Iran after he finished his education. He’d hoped to become a professor and run his own company.

Now back in Tehran, he isn’t sure how to move forward. He is working with advocates to determine whether he can get his visa sorted out.

“I have lost my job. I have lost my money. I have lost everything,” he said. “My wife is in the US. We don’t know what we should do. The only solution might be my wife coming back—and destroying her dreams.”